The Appeal of Collectible Card Games (CCGs)

In elementary school, I was an avid baseball card collector. There were few greater joys than opening a fresh pack of Topps baseball cards: the crinkling of the package as I carefully opened it to avoid any damage to the cards, the stick of third-rate bubble gum that I felt obligated to chew on for a minute or five, the expectation of a sought-after rookie card, the hope of picking up a duplicate of a valuable card to trade. My friends and I would pour over the statistics listed on the back of the cards. We’d negotiate and execute trades, curate our collections, compete over who had the most valuable collection, and speculate on which might be more valuable in ten years. I may have been slow with my times tables, but I could tell you Dwight Gooden’s ERA (Earned Run Average) and Alan Trammell’s BA (Batting Average) without hesitation… and I knew what it meant. I was deeply invested. I even got my parents—both completely uninterested in sports—to sign me up for baseball camp one summer. (I was a decent pitcher.)

So, my younger son’s emerging obsession with the Pokémon card game last year came as no surprise. Collectible card games (CCGs)—also known as trading card games—combine two highly appealing activities: curation and play (Turkay, Adinolf, & Tirthali, 2012). In 2002, researchers at the University of Cambridge concerned with children’s waning interest in the natural world and the “potentially grave consequences for biodiversity conservation,” conducted a study of 109 primary schoolchildren’s knowledge of British wildlife compared to Pokémon characters (Balmford, Clegg, Coulson, & Taylor, 2002, p. 2367). The findings of the study carried two significant messages: First, children have an incredible capacity for learning about creatures that are presented to them in an intriguing and entertaining way (i.e., on Pokémon cards); second, teachers and conservationists are doing a terrible job of making learning about the natural world engaging. The children much more readily identified Pokémon species than species in their native natural environment.

The Phylo Card Game

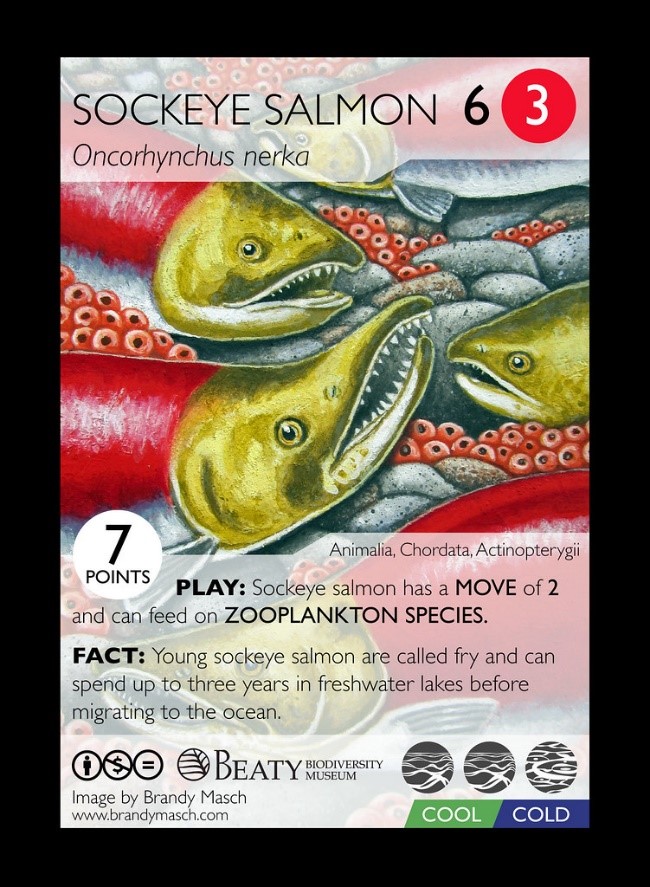

Instead of getting depressed about the deplorable state of children’s knowledge of the natural world, David Ng, an educator and molecular biologist at the University of British Columbia, was inspired to develop a Pokémon-style card game called Phylo: The Trading Card Game, which got underway in 2010 (Burgess, 2019). Ng decided against the original name of Phylomon for legal reasons. Using a crowdsourcing strategy, scientists, designers, and gaming experts worked together to develop a game based on the Pokémon model for teaching about biodiversity issues and other science-related topics.

Rules of the game and a starter deck are available at the Phylo Game website. Check out this video for the rules.

Does the Phylo Card Game work?

Does playing the Phylo Card Game impact people’s knowledge about and attitudes toward species, ecosystems, and conservation? In a mixed-methods quasi-experimental study, Callahan, Echeverri, Ng, Zhao, & Satterfield (2019) examined university students’ behaviors and attitudes toward playing Phylo. Upon comparing the attitudes and behaviors of students who had played Phylo compared to those who had learned about the same species in a slideshow, the researchers found that playing the game promoted greater positive affect and engagement. While there was no significant difference in species recall under experimental conditions, participants expressed their enjoyment in playing the game and desire to play more rounds of the game. Participants in the slideshow group did not express the same level of engagement. Motivation to engage further with the game suggests that greater long-term retention and deeper learning might be possible through playing the game than viewing the slideshow. Most importantly, the study verifies the notion that Phylo has potential use as a tool to effectively promote ecoliteracy and conservation goals.

If, as McGonigal (2010) indicates, the problem with many popular games is their lack of connection to the real world, then creative adaptations of the CCG model may be a way forward. Besides, as Turkay and colleagues (2012) point out, “From a design point of view, [CCGs] are simpler and cheaper to produce than digital games, as they cut out one third of the digital production trifecta: designer, artist, coder” (p. 3705).

The question is whether games like Phylo can ever come close to competing for kids’ attention given the massive financial success of Pokémon and other market-oriented products and all their spin-offs (video games, movies, toys, etc.). Given the severity of environment-related criIt’s probably worth a try.

References

Balmford, A., Clegg, L., Coulson, T., & Taylor, J. (2002). Why conservationists should heed Pokémon. Science, 295(5564), 2367. Retrieved from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/295/5564/2367.2

Burgess, S. (2019, September 18). To teach kids that know more of Pokemon than phytoplankton, David Ng, made a game of it. The Tyee. Retrieved from https://thetyee.ca/News/2019/09/18/David-Ng-Pokemon-Phytoplankton/

Callahan, M. M., Echeverri, A., Ng, D., Zhao, J., & Satterfield, T. (2019). Using the Phylo Card Game to advance biodiversity conservation in an era of Pokémon. Palgrave Communications, 5(79), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0287-9

McGonigal, J. (2010, February). Gaming can make a better world [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/jane_mcgonigal_gaming_can_make_a_better_world

Turkay, S., Adinolf, S., & Tirthali, D. (2012). Collectible card games and learning tools. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 3701-3705.