In the movie WarGames (1983), Joshua – a computer operating system – asks the main character, a teenager named David Lightman, an oft-quoted question: “Shall we play a game?” David replies, “Love to. How about Global Thermonuclear War?” To which Joshua responds, “Wouldn’t you prefer a nice game of chess?” How great would it be if gaming systems were more sensible than us? What seems clear, and not unsurprising, is that David prefers a contemporary high-stakes strategy game to an old-school abstract one.

“DEFCON 1” by bovinity is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

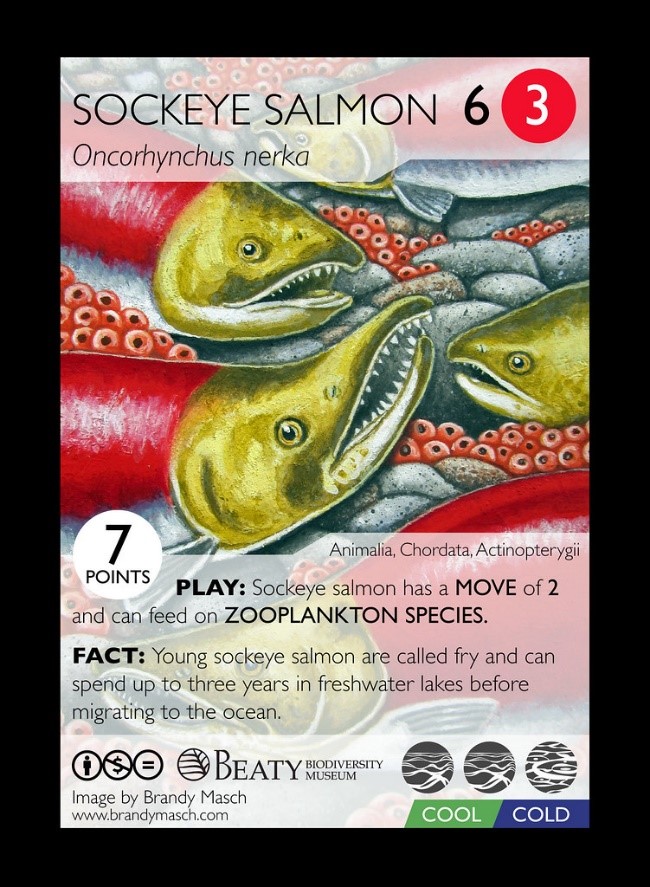

Today’s digital games have the power to excite and consume the attention of young people like no other form of entertainment, a fact which concerns many parents and fascinates many researchers. Harnessing the power of games – particularly digital games – for learning has emerged as an established area of study with a significant body of research. In this blog, I have attempted to survey a range of topics related to games and education or training. In the process I have learned a bit about how educational game developers are attempting to engage different types of learners in a range of contexts.

In WarGames, David’s desire to play a cutting-edge game over a traditional one should remind educators interested in using games for teaching that competing with the commercial gaming industry is an uphill battle. Today’s console games, with their high-end graphics and ever-evolving interactive and online features, provide hours of entertainment to users, both young and old. The solution, perhaps, is not to give up on or give in to digital games, but rather to find ways to bring game elements – play, challenge, competition, collaboration, story-telling, instant feedback, freedom to fail, and goal-orientation among others – increasingly into the instructor’s toolkit: to gamify the curriculum.

At the same time, gaming needs to be critically examined. Learners need to be made aware of potential mental and physical health risks related to gaming such as gaming disorder, defined by the World Health Organization (2018) as a pattern of gaming activities that have negative consequences on the user over a period of at least 12 months. While many educational game developers are quick to seize on the purported positive effects of games on learners, the potential disadvantages of games for users need to receive equal attention from researchers and developers. This, too, is a lesson of WarGames. It is only at the end of the movie that Joshua and David understand the futility of certain games, particularly Geothermal Nuclear War and Tic-Tac-Toe. It is from these games that Joshua and David learn that some games are not worth playing.

“Noughts and Crosses” by AdaMacey is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Blogging on educational games has provided an opportunity to explore the current state of game use in education, ponder synergies between gaming and learning, and consider how games and gaming elements may augment the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of learners.

Finally, keeping this blog has greatly enhanced my understanding of a complex and contested construct: educational games. This has led me to several questions, some more general, and some more specific. Below are a few:

- What are educational games?

- How can commercial games be used or modified for educational purposes?

- How can serious games be used or modified for educational purposes?

- What features or elements of games can be inserted into or serve as a structure for instruction?

- How can VR games be used effectively in learning and training interventions?

- In what ways can digital games be a form of assistive technology?

- Can games be both intentionally instructive and entertaining?

- What are the barriers to successful use of games in teaching and learning contexts?

- If games are not a choice, will instructors and learners accept their use?

- What is the relationship between gaming and socialization?

- How does gaming influence human behavior?

- When does gaming influence human behavior negatively?

- Can games heal?

The heroes of WarGames pose two last (and more philosophical) questions in this pithy exchange:

David: Is this a game or is it real?

Joshua: What’s the difference?

WarGames (1983)

References

Goldberg, L. (Producer), & Badham, J. (Director). (1983). WarGames [motion picture]. United States: MGM.

World Health Organization. (2018, September). Gaming disorder. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/features/qa/gaming-disorder/en/